Black Hands, White Myths: The Silent Riders of the American West

Reclaiming The Truth They Didn’t Teach About The Old West!

The image is iconic: a lone rider silhouetted against the setting sun, white hat tilted, rifle slung low. But the story that image tells is selective. Sanitized. Sold back to us on movie screens and Marlboro billboards. The real Wild West was far more diverse—and far more complicated.

The truth they didn’t teach? Black men helped build the frontier, ride the herds, and shape the culture. Yet their names were largely erased, their stories buried beneath a myth designed to elevate some and erase others (Britannica, Wikipedia).

White men were cattlemen. Black men? Cowboys. The difference wasn’t in skill—it was in power. Boy, after all, wasn’t a harmless word. It was a title used to diminish, to control, and to remind Black men of their “place” even while they mastered the terrain (National Park Service).

But once the term “cowboy” became romanticized, white America claimed it. And the Black laborers who had long embodied the role were pushed to the margins of myth. This is the truth they didn’t teach: That ‘cowboy’ was a badge Black men wore first, before it became an icon.”

By the late 1800s:

By the late 1800s:

1 in 4 cowboys was Black

1 in 3 was Mexican

Nearly all were underpaid, overworked, and overlooked (National Park Service, Britannica)

Many Black cowboys were former slaves or the children of the enslaved, drawn westward by the promise of comparative freedom and the chance to build something of their own. And yet, freedom was always conditional. While the West offered a break from the rigid caste systems of the South, Black cowboys were still hemmed in, pushed to the fringes of power, rarely promoted beyond trail cook or chuckwagon despite running full herds and, in many cases, training their white counterparts. They brought cattle-handling skills earned through generations of toil—and yet, they were still denied positions of authority. They formed all-Black trail outfits. And still: no foreman positions, no monuments, no headlines.

Even in the saddle, hierarchy held tight.

The myth of the cowboy: white, stoic, Marlboro’d and mythologized—erased this layered truth. It polished the boots of white cattlemen while consigning the rest to the dust. All-Black trail outfits existed. So did Black ranchers. But Hollywood didn’t pan the camera that way. And history, too often, followed its cue.

Can’t win for losing—a weary refrain that echoes across the Western plains, where the contributions of Black cowboys remain as rugged and resilient as the land itself, even when the credit never caught up.

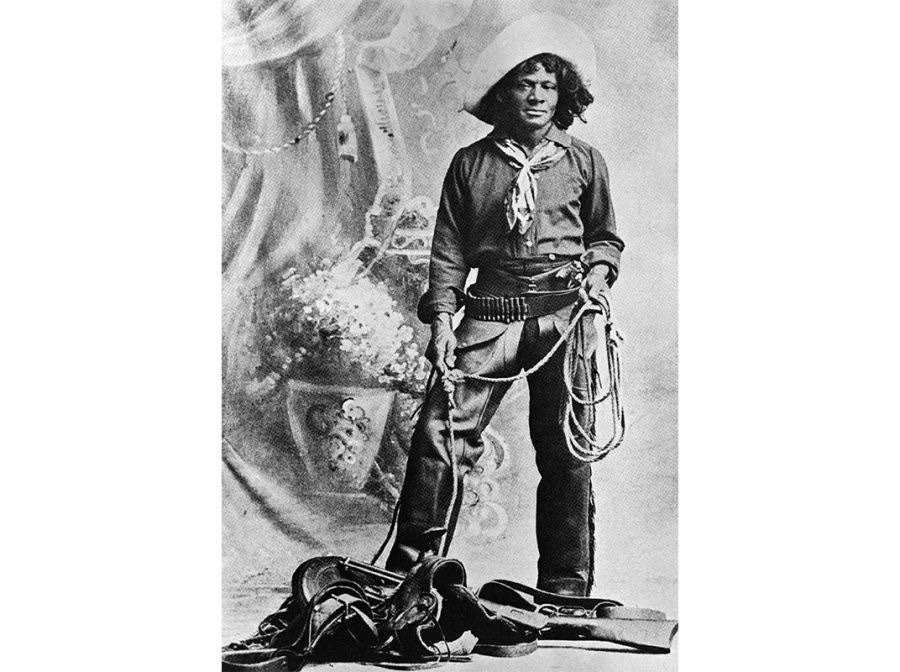

Nat Love: Rode Through the Myth. Born enslaved in 1854, he wasn’t just a cowboy—he was one of the few who wrote his own story. Known as “Deadwood Dick,” he broke wild horses, won rodeos, dodged bandits, and penned a memoir in 1907. His life was myth-worthy. But he vanished from the myth. He didn’t live outside the legend—he broke it open.

His story is emblematic. He rode the same trails, fought the same rustlers, broke the same broncos—but history tried to write him out of the frame. Unlike the sanitized cowboy mythos that Hollywood would canonize, Love’s narrative is gritty, full of bluster, but grounded in survival and skill. He wasn’t the exception. He was the evidence of a rule America refused to see.

And then there’s Bose Ikard, a man whose boots left real tracks across the Goodnight–Loving Trail. Born into slavery in Mississippi around 1843, Ikard became indispensable in the cattle drives that fed the legend of the American West. As Charles Goodnight’s trusted right hand, Ikard was more than a trail hand—he was Charles Goodnight’s trusted banker, scout, and protector. He fought off raids, guided herds, and carried money across dangerous country (TSHA). Yet, He never got the title “foreman.”

Goodnight himself once said, “I have trusted him farther than any living man.” That trust was immortalized in the epitaph he wrote for Ikard’s grave: “Never shirked a duty or disobeyed an order, rode with me in many stampedes, participated in three engagements with Comanches, splendid behavior.”

His life inspired a character in Lonesome Dove, but few know the man behind the fiction. Fewer still know how many Ikards history refused to name.

These men weren’t footnotes in someone else’s story—they were the story. But you wouldn’t know it if you learned your West from textbooks or TV in America. This is the truth they didn’t teach: That Black riders shaped the frontier and never got the credit they earned. This isn’t just history. It’s identity. When we erase Black cowboys, we erase Black belonging. We narrow Black possibility. We confine Black identity to struggle instead of legacy.

Reclaiming the stories of Nat Love, Bose Ikard, and the countless unnamed Black cowboys is more than historical correction—it’s an act of cultural justice. It’s how we confront the curated myths that have long sculpted American identity into something narrow, selective, and palatable for mass consumption. These stories were not omitted by accident; they were excluded by design, traded for a frontier fantasy that made whiteness synonymous with bravery, leadership, and grit.

To reclaim this history is to refuse amnesia. It is to insist that a nation cannot heal what it refuses to see. It’s how we remind ourselves and teach others, that Black lives weren’t just shaped by American history; they shaped American history. The cattle trails, the bronco rings, the borderlands—they were never white spaces alone. They were contested, co-created, and marked by Black hands, Black labor, and Black genius.

Reclaiming this narrative is about more than setting the record straight. It’s about asking why the truth was never taught in the first place, and who benefits from its absence. The truth they didn’t teach about the Wild West isn’t just historical oversight. It’s a deliberate narrowing of identity, legacy, and power.

The myth of the cowboy may sell better in theaters, but the truth rides deeper. Because the truth is tougher than legend. And the voices we resurrect today become the compass that guides us toward a more honest, inclusive tomorrow.

The truth they didn’t teach about the Wild West wasn’t just buried in the past. It’s buried in the stories we still tell. Because reclaiming history isn’t just remembering the past. It’s riding for the future, and if we want a future rooted in truth, we have to start by telling the truth they didn’t teach about the West, about Black history, about this country’s deepest myths.

So the next time someone tells you what a cowboy looked like, sounded like, or stood for: ask them whose stories they’re missing. Then go find them, tell them, share them.

Because reclaiming history isn’t just remembering the past. It’s riding for the future.

Sources:

Britannica – Black Cowboys: History, Facts, and Legacy

Wikipedia – Black Cowboys

National Park Service – Cowpoke History: Black Cowboys and Cowgirls

Britannica – Black Cowboys

BlackPast.org – Nat Love (1854–1921)

BlackPast.org – Bose Ikard (1847–1929)

Wikipedia – Goodnight–Loving Trail

Texas State Historical Association – Bose Ikard

CellyBlue-I Do Know This!

CellyBlue -- I do know this! Thank you so much for this illuminating history.

Armando grew up on the plainly stereotypical TV series of the 1950s, images that were so cleaned up that even the little boy knew they did not represent the crusty real life.

Your writing uncovers history in all its risk and human cost.

Your posts are always an inspiration to me!

One exception, from the novel and Movie "Lonesome Dove:" Joshue Deets, respected cowboy.