From Giselle to Justice: The Rise of Virginia Johnson

There’s No Place for You in Ballet (Virginia Johnson Went Anyway)

Did You Know!

Virginia Johnson didn’t just dance — she disrupted. “You’ve got all kinds of talent, but there’s no place for you in ballet”, she was told. It was meant to be a closing line — a quiet dismissal dressed as realism. Instead, Johnson made it her prelude.

Act One-Opening Scene: The Revolution Began in Slippers

Before she ever leapt across the stage as a principal ballerina, Virginia Johnson was already carrying history in her bones.

At three years old, she began ballet lessons in the Washington, D.C. living room of Therrell Smith, a pioneering Black ballet teacher who had studied under Mathilde Kschessinska, the Russian prima ballerina once close to the Romanov court. That thread, stretching from czarist Russia to Black America, wasn’t just lineage, it was subversion. Smith handed Johnson a legacy of imperial grace and fierce possibility, wrapped in a technique that few expected a young Black girl to inherit, let alone master.

By thirteen, Johnson earned a scholarship to The Washington School of Ballet, where she trained under Mary Day, one of the most esteemed ballet educators in the country. But instead of encouragement, Johnson was met with a verdict. As she prepared to graduate, Day told her: “You’ve got all kinds of talent, but there’s no place for you in ballet.”

That sentence should have closed the curtain. Instead, Johnson made it her overture.

Johnson didn’t just thrive where she was told she couldn’t — she changed what ballet could be.

Act Two: A Stage Where She Belonged

In 1969, just as she was studying at NYU, fate and vision intersected. Johnson was invited by Arthur Mitchell, the first African American principal dancer at New York City Ballet, to help found the Dance Theatre of Harlem (DTH). For Johnson, it was more than an artistic opportunity it was a reclamation.

Where The Washington School of Ballet had drawn boundaries, DTH erased them. Suddenly, Johnson was not “the only one” she was surrounded by dancers of color shaping a new narrative for classical ballet. Her talent, long filtered through skepticism, now took center stage with radical clarity.

She danced principal roles that carried both beauty and burden Creole Giselle became a vessel for cultural reinterpretation; Fall River Legend showcased her emotional range; Agon, choreographed by George Balanchine, confirmed she could command even the most abstract works with rigor and resonance.

Each performance was more than choreography, it was testimony. Her presence on stage said to audiences, critics, and young dancers watching: We have always belonged.

Act Three: Technique as Testimony

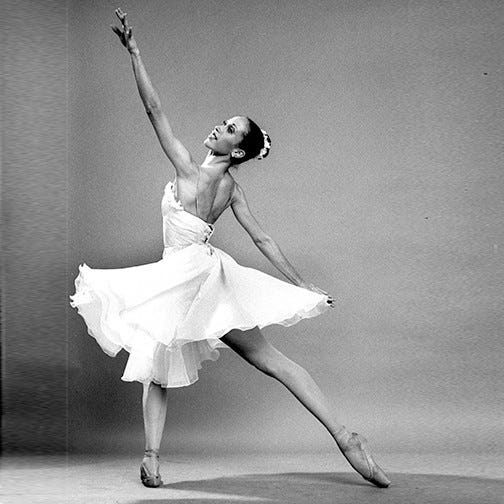

Virginia Johnson didn’t just perform ballets — she redefined what they could communicate. Her dancing was described as lyrical, intelligent, and emotionally expansive, a blend of classical precision and soulful depth that turned choreography into commentary.

In Creole Giselle, Johnson brought a new heartbeat to the role of Giselle by reframing the romantic tragedy through a Creole lens. It wasn't just a cultural adaptation; it was an assertion that Black dancers could inhabit the classics with authenticity and excellence. Her movement carried grief, love, and ghostly elegance in equal measure —critics called her performance “hauntingly beautiful.”

Her work in Agon, George Balanchine’s abstract neoclassical piece, pushed even further. With angular lines and daring timing, Johnson stood shoulder to shoulder with the most elite technicians in ballet, showing that Black bodies could command even the most cerebral of choreographies. This was no longer about proving she could do it, she was doing it better than anyone else.

Johnson infused dramatic storytelling with physical finesse in every role she danced. Every arabesque was layered with meaning, every lift felt like resistance. She didn't just dance roles — she embodied them, reshaping ballet into a canvas that bore her fingerprint.

And she did it all while navigating a world where her very presence challenged the traditions she excelled in.

Final Act: A Legacy That Leaps Beyond the Stage

Virginia Johnson didn’t just break barriers, she built bridges. Her performances redefined what ballet could express and who it could represent. Today, dancers of all backgrounds: Black, brown, queer, disabled, and beyond cite her as proof that excellence doesn’t require erasure.

Her legacy means:

Representation with Rigor: Seeing Johnson command the stage with lyrical power and emotional depth showed that dancers of color could not only perform the classics — they could transform them.

Global Inspiration: From Harlem to London, her performances resonated across cultures, proving that ballet is not a monolith but a language that adapts and includes.

Intellectual Artistry: Johnson’s commitment to character research and narrative depth taught dancers that technique is only half the story — intention is the heartbeat.

Visibility as Possibility: As one dancer put it, “Seeing Black and brown bodies on stage in such a graceful element is so beautiful to see. It changed my life.”

Even after retiring as artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem in 2023, Johnson’s impact continues. Her work with The Equity Project and her mentorship of emerging artists ensures that ballet’s future is more inclusive, expressive, and bold than ever.

She planted seeds in pointe shoes — and now, entire generations are dancing in full bloom.

Final Movement: Legacy in Motion

Virginia Johnson didn’t just dance roles — she danced revolutions. Her performances in Creole Giselle, Fall River Legend, and A Streetcar Named Desire weren’t just artistic triumphs; they were cultural interventions. She reimagined ballet’s aesthetic boundaries and shattered its racial gatekeeping, proving that classical technique and emotional depth were not confined to whiteness.

She once said, “I thought of myself as a normal person pursuing a dream… and had to have these reminders thrown at me that I wasn’t.” That tension — between identity and imposed limitation — echoes across time.

Today, her legacy lives in every dancer who steps into a studio believing they belong — because Johnson made it so.

For dancers of color, she is a blueprint: proof that excellence doesn’t require assimilation, and that presence can be protest.

For dancers of all kinds, she is a reminder that ballet is not just about form — it’s about intention, research, and storytelling. Her commitment to character work and historical context elevated ballet from spectacle to substance.

For the next generation, she planted seeds of possibility. As one dancer said after seeing DTH perform: “Just seeing Black and brown bodies on stage in such a graceful element changed my life.”

And for me, Johnson’s legacy mirrors my own mission. Johnson reclaimed space through movement; I reclaim memory through words. She danced through erasure; I write through it. Her story is not just inspiration — it’s affirmation.

“There was a generation of little girls who didn’t see brown ballerinas… they didn’t have that seed planted of ‘I could be up there too.’” — Virginia Johnson

Reference Sources:

Dance Theatre of Harlem. “Virginia Johnson.” Dance Theatre of Harlem. Accessed July 11, 2025. https://www.dancetheatreofharlem.org/people/virginia-johnson/

Johnson, Virginia. “Relevétions.” Pointe Magazine, Spring 2000. Reprinted March 13, 2025. https://pointemagazine.com/relevetions-virginia-johnson-pointe/

Keefe, Maura. “Virginia Johnson.” Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive. March 2017. https://danceinteractive.jacobspillow.org/themes-essays/women-in-dance/virginia-johnson/

Ipiotis, Celia. “A Day in the Life of Dance: Virginia Johnson Reflects on Her Storied Career.” The Dance Enthusiast, April 17, 2023. https://www.dance-enthusiast.com/features/day-in-the-life/view/Dance-Theatre-of-Harlem-Virginia-Johnson-Groundbreaking-Ballerina-

MOBBallet. “Virginia Johnson.” MOBBallet.org. Accessed July 11, 2025. https://mobballet.org/index.php/2017/02/26/virginia-johnson/

Wikipedia contributors. “Virginia Johnson (dancer).” Wikipedia. Last modified June 28, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Johnson_(dancer)

CellyBlue-I Do Know This!

Let’s elevate voices that weren’t meant to be forgotten. Let’s make legacy louder. Every story here is a step toward justice — and the rhythm belongs to all of us.

Brava, Virginia! Thank you, Celly, for sharing her story.

CellyBlue -- I do know this! You tell the story of Virginia Johnson with the beauty and high dignity her gift and singular achievements earn.

Thank you so much for sharing the beauty of the culture of ballet in the heritage of Harlem.